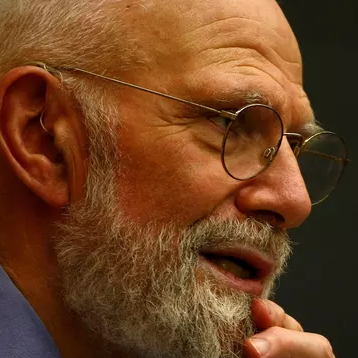

A friend loaned me her copy of Gratitude (Knopf, 2019) by Oliver Sacks. Its spare 40 pages hold four beautiful little essays, each a memory or reflection written by Sacks in the closing years and months of his life. Though each essay yields many messages, some resonated strongly.

A friend loaned me her copy of Gratitude (Knopf, 2019) by Oliver Sacks. Its spare 40 pages hold four beautiful little essays, each a memory or reflection written by Sacks in the closing years and months of his life. Though each essay yields many messages, some resonated strongly.

1. “Mercury” — Since boyhood, Sacks connected each birthday with the element of the corresponding atomic number. At age seventy-nine (79 is gold) he reflects on turning 80 (mercury), and . . . “begin[ning] to feel, not a shrinking but an enlargement of mental life and perspective . . . A time of leisure and freedom, freed from the factitious agency of earlier days, free to explore whatever I wish, and bind the thoughts and feelings of a lifetime together.”

2. “My Own Life” — Sacks learns that his nine-years-ago cancer has returned and metastasized, leaving him only a few more months . . . “I have been able to see my life as from a great altitude, as a sort of landscape and with the deepening sense of the connection of all its parts . . . I feel intensely alive, and I want and hope in the time that remains to deepen my friendships, to say farewell to those I love . . . To achieve new levels of understanding and insight . . . I feel a sudden clear focus and perspective. There is no time for anything inessential. I must focus on myself, my work, and my friends. I shall no longer look at the NewsHour every night. I shall no longer pay any attention to politics or arguments about global warming. This is not indifference but detachment . . . My predominant feeling is one of gratitude. . . . Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

3. “My Periodic Table” — “ . . . and now I am terminally ill, at the age of 82 [lead]. I have to say that I am not too exercised by “the hard problem(s)”. Now, in his closing years, Sacks finds scientific research and problem solving much less interesting, partly he explains, because the problems will be solved in the future when he won’t be here. However, . . . “A few weeks ago, I saw the entire sky “powdered with stars” . . . This celestial splendor suddenly made me realize how little time, how little life, I had left. My sense of the heaven’s beauty, of eternity, was inseparably mixed for me with a sense of transience — and death . . . I have a beautifully machined piece of beryllium (element four) to remind me of my childhood, and how long ago my soon-to-end life began.”

4. “Sabbath” — Sacks’ Orthodox parents, intensely religious, rejected his homosexuality. Sacks left the religious community, moving from London to Los Angeles to study neurology. After relocating to New York and working in a chronic care hospital in the Bronx, he wrote about his patients in Awakenings. This book launched his vocation as neurologist and storyteller. In this fourth essay Sacks musings meander through his childhood and later life, reminiscing on the significance of the Jewish traditions to his friends, his family, and now to him. “I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.”

§

I read my first Sacks book in Berkeley in the 1980s — The Man Who Thought His Wife Was a Hat. Most recently was Hallucinations in 2015. Sacks had a knack for new interpretations of familiar events. His writings are exciting, insightful, and for many readers, memorable.

I read my first Sacks book in Berkeley in the 1980s — The Man Who Thought His Wife Was a Hat. Most recently was Hallucinations in 2015. Sacks had a knack for new interpretations of familiar events. His writings are exciting, insightful, and for many readers, memorable.

Now with these four posthumously published essays, he’s swept me into a reflective journey.

Oliver Sacks, I’m grateful you were in my life. You were, and still are, one of the countless people who have unknowingly made me who I am. Wherever you are, I thank you.

And I thank you, readers, for joining me. As always, I appreciate and value receiving your input, your thoughts, and experiences. How does gratitude play in your life?

me, Barry Phegan