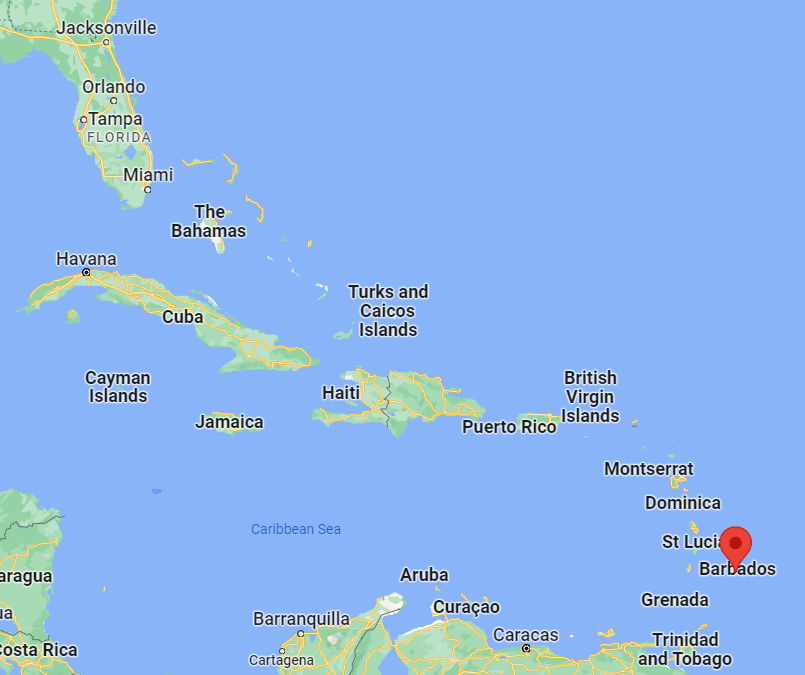

Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados is ready to default on her country’s national debt (NYT, July 31, 2022). After being hit by a series of increasingly devastating hurricanes, Barbados borrowed heavily to replace damaged infrastructure. Mottley now questions why Barbados should continue borrowing to meet debt payments. These crippling debts stem from more frequent and severe hurricanes caused by other nations’ industrial dumping.

Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados is ready to default on her country’s national debt (NYT, July 31, 2022). After being hit by a series of increasingly devastating hurricanes, Barbados borrowed heavily to replace damaged infrastructure. Mottley now questions why Barbados should continue borrowing to meet debt payments. These crippling debts stem from more frequent and severe hurricanes caused by other nations’ industrial dumping.

It’s a powerful moral question — in a world where power, not morals, dominates.

Is it legitimate that companies profit by externalizing costs, foisting them onto people, nations, and the environment? Can we question this tradition, or is it now fixed into our cultural assumptions as an untouchable right of people and companies?

Changing cultural norms and traditions isn’t easy. Here it confronts the immense power and control of corporate lobbies. But we cannot address long-term global issues such as climate change, inequity, and inequality without questioning the cultural assumption that externalizing expenses is a corporate right. That’s why Mottley asks the International Monetary Fund to, “Forgive our debt. Charge it back to the profiteers who brought us to ruin.”

Closer to Home

Here in the US, we suffer trillions of dollars in annual losses from intensifying forest fires, floods, and drought, all directly attributable to climate change from atmospheric pollution. When dumping is free, manufacturers and mineral extractors tailor their processes to maximize this pollution — which they call externalized costs — because every expense they avoid goes directly to corporate profit.

Externalizing is so profitable that high pollution manufacturers such as paper, glass, and chemicals flock to states, such as Louisiana, which don’t enforce federal EPA regulations. Like the manufacturers, these poor states then externalize their now increased health and social costs to richer states such as California, which subsidize poor states through federal tax transfers. A tiny fraction of the vast corporate profits that come from ignoring EPA regulations pay local politicians to defund state EPA enforcement. The financial return on these political contributions is huge.

Pollution is Pure Profit

Between a third and a half of corporate profits come from these externalized costs such as pollution. Repairing the damage from that corporate profit comes from you and me, the taxpayers and sufferers worldwide.

It’s cheaper to stop the dumping at the source rather than try to clean up afterward. It’s cheaper to have sustainable manufacturing processes than deal with climate change, sea level rise, flooding, forest fires, heat waves, hurricanes, and chemical-induced illness. But that’s the 30,000-foot big-picture level. Dumpers live at ground level. They maximize pollution (maximize profit) while others pay the cleanup bill, and that tab is enormous. It currently runs at trillions of dollars annually, and this is only the beginning of the rapidly growing costs of climate change.

Additionally, if you’ve had friends who’ve lost their houses to fires or floods, you know the emotional and social costs can be many times the cash losses.

Bad Neighbors

We don’t tolerate neighbors throwing their trash into our yard, expecting us to pay for the cleanup. We should do the same with corporations and other polluters. That’s how Mia Mottley sees it. I agree with her, but doubt we have the political will to reign in the dumpers, let alone seek retribution (in her case, foregoing Barbados’s unpayable debt).

We don’t tolerate neighbors throwing their trash into our yard, expecting us to pay for the cleanup. We should do the same with corporations and other polluters. That’s how Mia Mottley sees it. I agree with her, but doubt we have the political will to reign in the dumpers, let alone seek retribution (in her case, foregoing Barbados’s unpayable debt).

It seems only fair that we should each pay our way. But politics is money. Corporate lobbyists show up at politicians’ doors with bags of cash, while the average citizen usually brings a complaint. As a politician, who would you prefer? Once again, “You get what you pay for.”

Despite this, I’m idealistic and hopeful (naïve?) enough to imagine that our society will eventually move towards sustainable production processes, where polluters pay the real cost of their pollution. That’s not the world we live in, but perhaps we can discuss such possibilities — without the conversation becoming more fuel for tribal division.

But we will never agree on solutions if we can’t agree on the problem. As I see the problem, the fox is in the henhouse, and we don’t know how to name it and get it out.

Thank you for reading.

Barry

Add Your Name below to my list to know when I have posted a new blog.